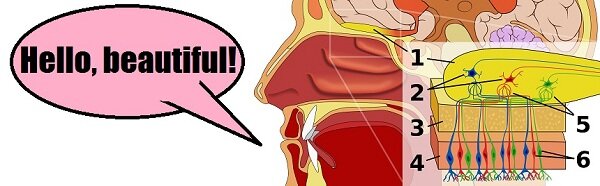

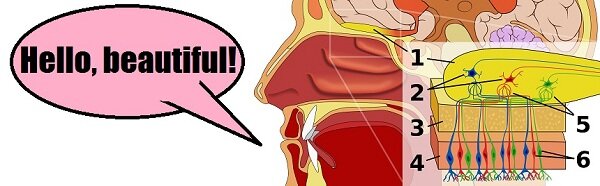

From an original image by Ignacio Icke. Caption improvised by Bubba.

As I started to write this, a hippie chick sitting near me saw me pull out my ear buds and asked me if I’d heard “what I just told that other man…about the perfumes?”

There’s just no good answer to that question.

When I miserably sighed out the only real answer I could give — the honest one, since I’d been listening to Skinny Puppy and couldn’t hear shit the first time she ran through it — I was treated to about a five-minute lecture on the small business she apparently just started, importing body oils from a group of Sufi producers in Tangier, Morocco. “The Sufis believe that they brought scent to the Earth…and, now, whether that’s true, I don’t know, and I don’t really care, since I’m not a Sufi.” She gave me three of her flyers, “For you and your friends,” packed with velo-wrapped samples that look disturbingly like enormous ketosis strips. Since I doubt my new friend would be amused if I hauled that shit out and peed on them, the samples are currently stinking up my keyboard, while I try to write blog posts.

This, of course, is a bizarrely Sufi-esque string of events for the Universe to hurl my way. After all, I’d already decided that I would title my blog post “Smell, Don’t Tell,” because it rhymes. And that’s what The Cosmos whacked me with, as if to say “Oh, yeah, fucker? Smell THIS!” Right now, incidentally I’m more inclined to re-title it “The Smell from Hell,” because while I’m as happy as the next guy to huff a little of the Breath of Life, the overpowering scent of African black musk is a little intense when one’s trying to operate a human brain on nothing more than a recoil starter primed by six liters of coffee.

Anyway, so that intense smell that I’m huffing right now? It makes me dizzy, and makes me think, “Whirling dervishes, harem girls, the Call to Prayer, teenage hippy chicks shimmy-shaking on my dorm room bed in the lyrical years before my friends and acquaintances all seem to get multiple chemical sensitivity.” Back in those days, stinking up a room was the Goddess-given right of every college student, and it was done with great prejudice: with body oils, perfumes, cigarettes, incense, pizza lifted from the Dining Commons, copious gurgling bongloads from hell, day-old burritos, discarded nitrous canisters, Jack Daniels, and Boone’s Apple Wine — plus a few scents far less pleasing. It was positively boner-inducing, though admittedly I was in my teens and early twenties, so what wasn’t?

One of the traps I think many erotica writers fall into is forgetting to describe certain sensual details of the scene. However, the opposite crime is also possible. Many writers in all genres can put too much sensual detail for my taste — or, far worse, just pick those sensual details out of a hat and describe them in hackneyed ways that have been done to death. When someone walks into their parents’ house and smells the comforting scent of Mom’s cooking, GAAHAHAHAHHAHA! I’ve heard it a thousand times. The scent is there to communicate information, supposedly, but it’s not real, because it’s been grabbed from the fiction writer’s paint-by-numbers set, not re-experienced and re-imagined the way sensual details, and particularly olfactory ones, should. But you don’t have to create the perfect sensory description for a scene to be augmented by olfactory details — in fact, your quarry just has to think he or she knows what the thing you’ve described smells like, which can be based on nothing more than your description. All you have to work with is words, so words get to stand for every sense you could possibly engage…accurately or inaccurately, and I’m not so sure it really matters.

In my opinion, nowhere is that more important than in erotica. Nor is there a more powerful tool in the erotic writer’s toolbox than olfactory details, freshly imagined (or…ripely, if you’re into that) and rendered in original terms. Smell is a powerful subconscious motivator when it comes to sexual activity, and if you can get across the scent of something that causes a sexual response — not so much in your reader, but in your protagonist — then you’ve got a live wire right into your victim’s backbrain.

Did I say “victim?” I meant, of course “reader.”

There’s a danger more subtle than just hacking out the same predictable phrases to describe the sent of a campfire, sea breeze, boudoir, French whore, weightlifting stud or stinky back alley, however. It’s adding details that shouldn’t be there.

In my opinion, scents in very tightly-written plot-driven fiction should be there to communicate information, rather than just provide window dressing. Humans do our thinking with our bulbous cortexes a lot — some of us more than others. If sensual details (of ANY sense — but smell is particularly important here) don’t communicate information related to plot, character or setting, then they’re just there to be there. In that case, to my way of thinking, virtually any sensual detail can potentially be one of Chekov’s many unfired pistols — it’s there, taking up space, for no good reason.

Maybe the author just decided to be a Smell Commando this week, describing how the scene smells because “it’s important to the millieu.” It might be, and it might not be, but the reader shouldn’t wonder. The description of a scent should either be so compelling that it creates a concrete response in the prey (er…”reader”) or it should be a piece of story information in addition to helping transport one into the scene.

The tendency to describe sense-experiences rather than information-experiences was one of the things that alienated me from poetry, actually, back when I used to be very interested in it. I was unsettled by the form’s tendency to focus on experiential details of sensual significance only insofar as they had sensual significance, rather than insofar as they communicate information. It made me feel like as a writer and a reader, I was wasting my time. Not all readers are as alienated by excess sense information as I am, so take it with a grain of salt. And I’ve also heard many prose writers who say they learned a lot of valuable descriptive techniques by studying poetry.

But as a bona-fide Brainiac, I grab information from the sensual world and stuff it into this mammoth computer I call a brain. Or, more specifically, a frontal lobe — and no, I don’t stuff it in the lobe you’re probably thinking of, perv. Yes, indeed, the “lobe” you might be considering is indeed wired pretty strongly to my other frontal lobe, about forty inches north. Yours may be too, whether your equipment includes a “lobe” or…whatever.

But humming deep in the chasms of your brain is a whole universe of non-verbal arousal cues that can be communicated through fiction over and above what a smell can communicate informationally. That’s because smells can do all three things. They can a) communicate information, b) draw a reader into a scene, and c) have no specific plot significance in and of themselves, but hold a significance within the machinations of the plot itself, in that they draw a parallel between an early scene and a late scene.

For instance…check it: This guy — I’ll call him “Bubba” — walks into an apartment and smells African black musk. That tells you that the protagonist knows what African black musk smells like. Bubba probably knows what African black musk smells like for a reason. That gives you an opportunity to hint at why Bubba knows, or leave it unstated. The place probably also smells like African black musk for a reason. Ditto.

You can describe the smell itself, or not, depending on how evocative the term is, and how commonly known the smell is. Maybe the reader knows what African black musk smells like. Maybe not. I sure as hell didn’t until about fifteen minutes ago. But the term itself holds an automatic sensual significance for me, and not just because I’m huffing it right now. The very name is evocative. “African black musk.” Hello, beautiful. I think I know what African black musk smells like, even if I don’t. (Though, to be fair, I do. So will everyone who gets within 40 feet of me for the next 72 hours.) Terms might be less evocative or more evocative, but to my mind the evocation that the term and your description provide are far more important than whatever the stuff smells like.

So here’s what that does for the person reading about the guy who just walked into the stinky-musk apartment:

Information is communicated: Bubba knows what African black musk smells like. For some reason. The apartment smells like African black musk. For some reason. Bubba’s first love was an African musk ox! And the woman who lives the apartment, where Bubba is, say, delivering a Hot Tomato Pizza? Maybe she’s secretly an African musk ox, too! (Bubba’s pizza’s deep dish, incidentally with lots of anchovies…were-oxes love anchovies. Incidentally, it smells great, but we’ll cover that particular aroma in some other column, maybe.)

2) The reader is drawn into the scene: Whether or not the reader knows what the stuff smells like, just having the ol’ sniffer engaged may get a nosehook on ‘em, if you know what I mean. Plus, when Oxana says “Gee, Mr. Pizzaman, I don’t have any money to pay for my pizza,” it’s already been established that she’s having an anti-rational, pro-sensualist effect on Bubba, so when the funk music starts, the sex isn’t just, like, random.

3) …and, lastly, you’re provided with a fully loaded and primed Chekovian Blunderbuss…later, after his fervent tryst with the beautiful and mysterious “Oxana,” Bubba can stand there in her living room spinning with joy while holding his Hot Tomato Pizza red uniform shirt think “Gee, I wonder why this girl I’m falling for smells like African musk!?”

Then voila! It hits him! Full moon’s out, see, and out of the bedroom bursts this giant musk ox, see? And it spots Bubba spinning for joy and waving his red Hot Tomato Pizza uniform shirt, and…

What…you were expecting Gift of the Magi?

My biggest news right now is that The Playground is released through Decadent Publishing! The 1Night Stand series is apparently very popular and when I met Kate Richards and Valerie Mann at Erotic Authors Association Con in Vegas last year, they convinced me to write something for them.

My biggest news right now is that The Playground is released through Decadent Publishing! The 1Night Stand series is apparently very popular and when I met Kate Richards and Valerie Mann at Erotic Authors Association Con in Vegas last year, they convinced me to write something for them.

Recent Comments